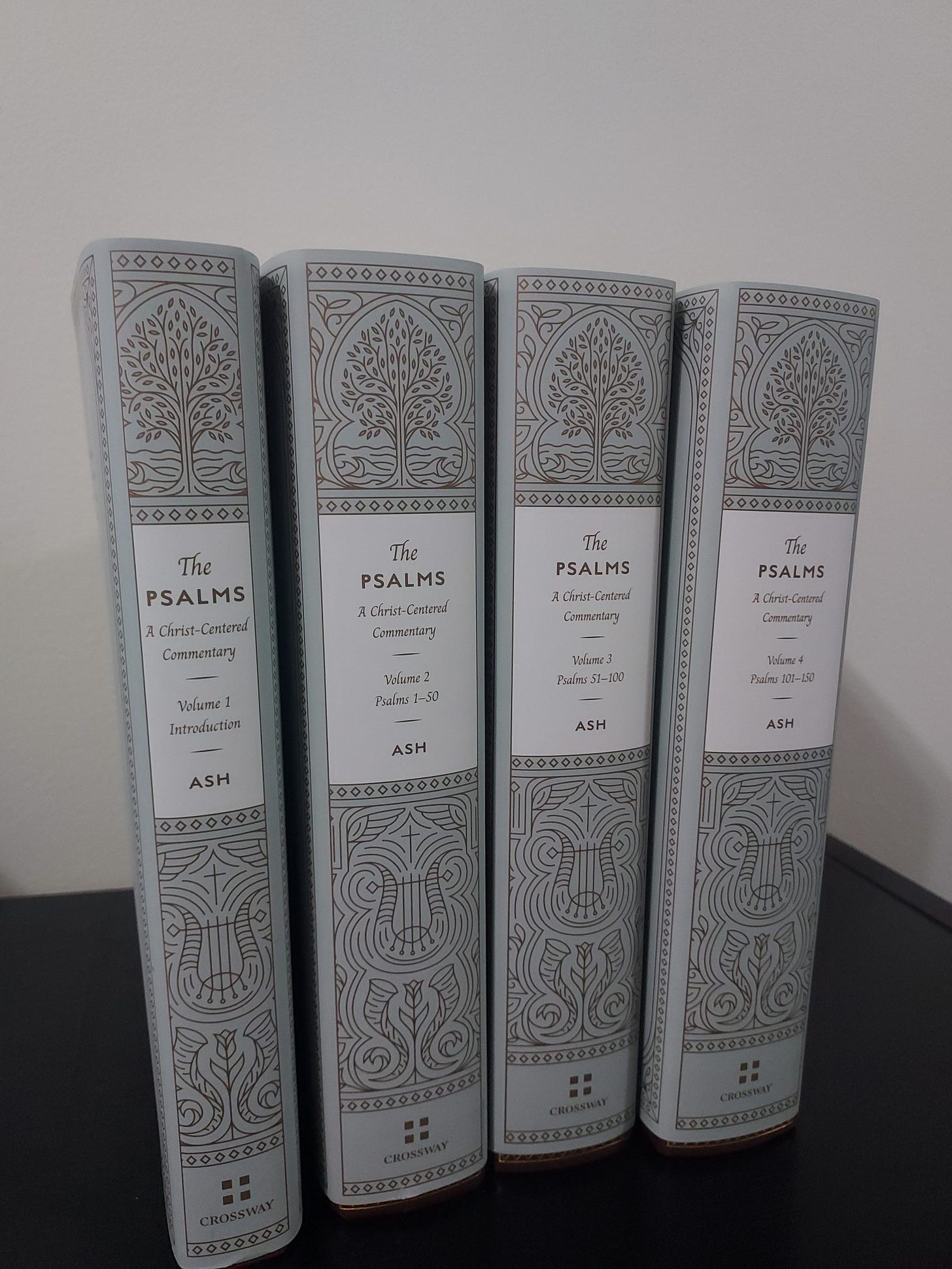

Psalms: A Christ-Centered commentary

Book (p)re-review (Christopher Ash)

"Two convictions underlie this commentary: that the Psalms are essential to the life of the Christian church and that Christ is central to the Psalms" (xiii)

About a year and a half ago I began to wonder if I should write a book. I saw that there wasn't really a commentary on the psalms that took these two convictions seriously, and that worked and explained its way through the Psalter with those two things in mind, i.e. that the Psalms are the song and prayer book of the Church, and that Christ is the key and center to them.

Then I discovered Christopher Ash's work on the psalms, in particular his two volumes on Teaching Psalms, and his popular-level study Psalms for you, which I led a small group through most of earlier this year. Wonderful, I thought, here is exactly what I was looking for and now I don't need to write it.

Well, I'm very glad to see that Ash did not stop there, but has carried such work to a full-blown commentary in four-volumes. Not least, I don't need to write it myself. And, because it's a four-volume work this is not exactly a review, as I don't pretend to have read the several thousand pages.

Volume 1 is a fine book all by itself. It argues for Ash's two central convictions, discusses method, relates the Psalms to areas of Christian doctrine, tackles significant questions (such as can Jesus pray psalms of penitence, and what do we do with the imprecatory psalms); there's a historical overview, and then some concluding matters.

Instead of working through and commenting on the preface volume, I'm going to turn my attention to the commentary proper (vols 2-4, 50 psalms a piece), and pick three psalms to read. I'm not going to comment so much on Ash's specific commentary, but make some observations about the commentary as a book. E.g. you are not about to get comments on 3 psalms, but comments on a commentary on 3 psalms. Confused? Just read on.

Psalm 42-42

Why together? Ps 42 has no superscription, unique in this section of the Psalter, and it is closely connected with a refrain (42:5, 11; 43:5). But most Hebrew texts and the LXX divide them. Ash treats them together, but also with some distinction.

Part of Ash's approach is to begin by orienting you to a Christocentric reading of the psalm, before he turns to the psalm proper, and here he does so by focusing on Jesus' grief in the context of Gethsemane, and in light of Hebrews 2:17-18's sympathy with us.

Ash's comments are clear, follow the context and contour of the psalm in its form-as-given, and makes good use of footnotes and references. The fact that Ash isn't an OT Scholar or a Psalms expert, but writes as a (very)-well educated non-specialist makes this type of commentary an excellent middle-ground between the wealth of research lying behind it, and the (also) non-specialist reader.

The interpretive references to Jesus are judicious: neither pervasive and overwhelming, nor tacked-on, but they arise from reading the text in light of Jesus. There's a goodly amount of biblical cross-referencing for allusions, and apt quotation from commentators, new and old, on the Psalms.

The commentary on the psalm ends with Reflection and Response, where Ash moves to give some thought to the theological notes that arise from the text, and how this integrates with the individual believer and the church as a whole.

Psalm 56

Ash's quotations from commentators ranges from the patristic to the reformation to the 'great saints' of the post-reformation protestant traditions. In this psalm, following Augustine's lead, Ash understands the necessary move to be from David to Jesus. Ash's notes comment on individual phrases, Hebrew words where necessary (without being anywhere near a technical Hebrew commentary), structure, and theology. All without being overly long or wordy. It's quite a feat.

The main pattern of hermeneutic goes something like this: here we see David in trouble, in fear, and trusting in the midst of that fear. This, in turn, becomes a type for Christ, who likewise experiences these things in their fullest realisation. We, in turn, bring our similar experiences to Christ, and in him, in trust and confidence, pray with him and through him this psalm for our benefit.

Psalm 109

Probably (along with Ps 137) one of the most difficult psalms to work out what to 'do' with, as it has incredibly (to our ears) shocking language of invective. Ash refers to his work in the introductory volume, for his case on how and why we pray these psalms too, in Christ, and here he applies that hermeneutic. It's a psalm in which David invokes God's judgment on his accuser(s)/betrayer(s). Ash takes this as ultimately both (a) prophetic and (b) paradigmatic. Firstly, it's prophetic, as the NT takes the psalm and applies it to Judas. David speaks prophetically of Christ responding to his accusers and betrayers, especially Judas.

For Ash, then, this is a psalm calling for justice, and as such it calls upon God to do what he has done and has promised to do - bring justice. It's primary fulfilment is in on Jesus' lips, in relation to Judas, but its "overflow" is as a prayer of the church in solidarity with Jesus, for the persecuted church in particular. And yet it's not a psalm prayed against "named individuals". I love the quote from Calvin here: "let them rather leave room for the grace of God... it may turn out that the man, who to-day bears towards us a deadly enmity, may by to-morrow through that grace become our friend."

Conclusion

As I said earlier, I think this is a great *concept* and having read Ash's work on the psalms so far, and dipped into this one here and there, I have no doubt that this 4-volume work is about to become a close companion in my prayer life.

I got to meet Christopher the other day, which was cool. He was really warm and curious.

These sound like a must have