Northern Ireland. The Fall of the Berlin wall. Perestroika, Glasnost, and the collapse of the USSR. Sarajevo, Kosovo, the breakup of Yugoslavia. Rwanda. Kuwait. Iraq. Afghanistan. Ukraine. Palestine and Israel.

These are just the most prominent wars that I can remember in my lifetime. We live in a world of war, violence, and death. It hasn't changed, and it is not likely to change that much in the future. Humans are wont to kill each other, and increasingly better at doing so.

Much of my early intellectual formation took place (like lots of people) in my youth, when I was reading a huge range of philosophy, literature, and theology (as I became Christian). It's then that I got convinced that Christians ought to be pacifists. I don't think there's any other way to authentically live out the ethical teachings of Jesus.

There's not just one variety of Christian pacifism though. There's a whole garden of the. Which is why Miles Werntz's book, A field guide to Christian nonviolence is valuable in laying out eight different 'streams' that differ and overlap and diverge. But today we're going to talk about one variety.

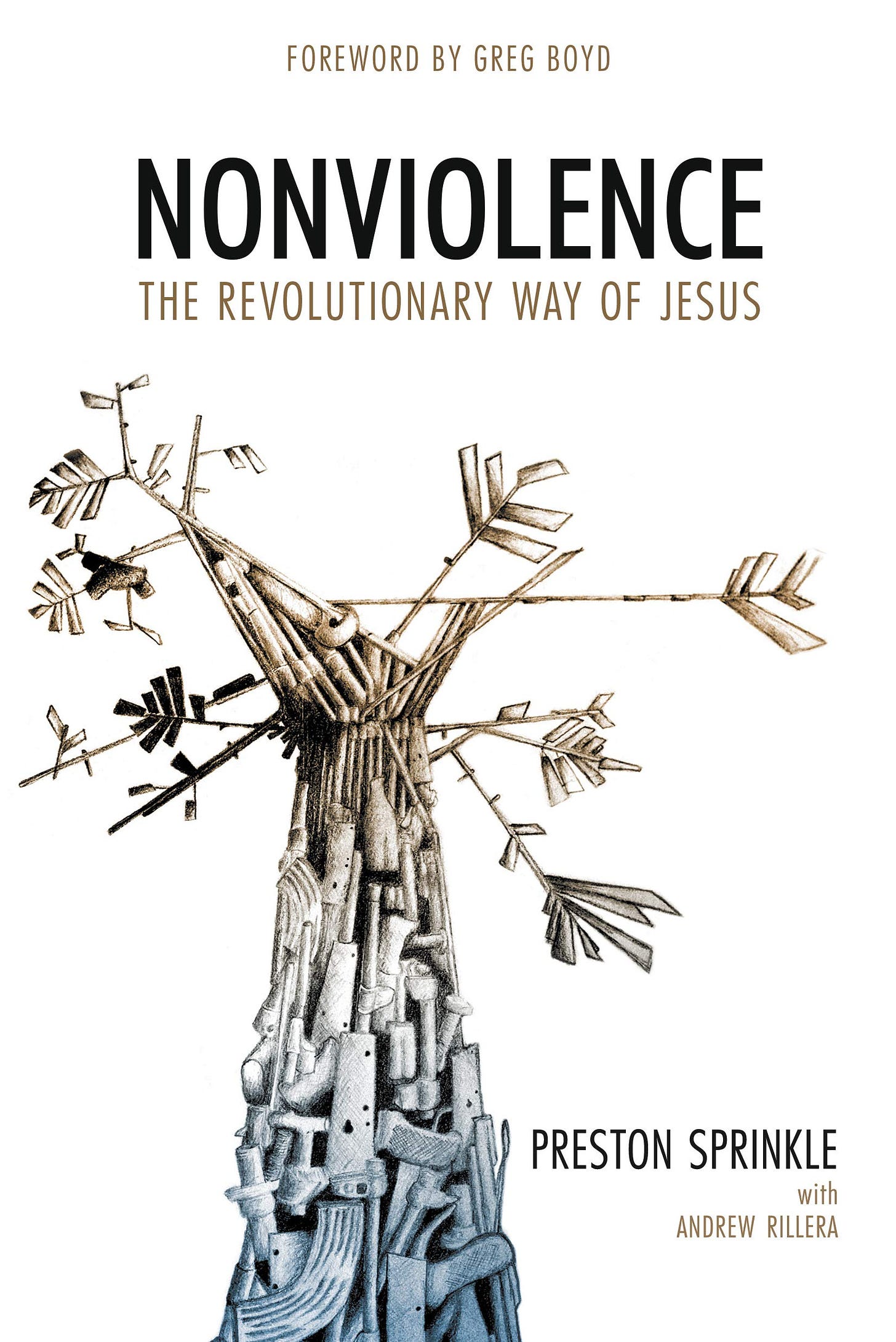

Preston Sprinkle, who these days mostly just seems to run a podcast and write books about Christianity and sexuality, wrote a fine popular level book some years ago (2013), "Fight!" which is an ironic title for a book laying out a case for non-violence within a mostly evangelical framework. It was re-released in 2021, with a new forward. I don't think the contents have changed substantially. What I appreciate about it is that it's relatively readable for most people, it presents a straightforward argument that follows a biblical narrative framework, and it's operating in an overall theological framework that's probably the most adjacent to my own and those around me.

Beginning with a biblical-narrative framework means beginning with the Old Testament, and taking it seriously. How do pacifist Christians read the OT? Well, in a variety of ways, but Sprinkle offers a relatively decent one. He begins with a vision of shalom, of the holistic peace vision that is there in Genesis 1-2, and lost so devastatingly in Gen 3, before he begins to work through the Patriarchs until we get to the Mosaic Law.

The reading of the Law here is both important and challenging. Essentially Sprinkle (following others), makes three moves:

The Law needs to be understood as God's accommodation to the people of the time. We read the OT Law in relation to other Ancient Near Eastern cultures and ethical systems.

The Law undoubtedly improves on the ethical systems of its time and place.

But we need to consider the intention of the Law, especially in light of God's intention, which is an Edenic ideal, not just a Mosaic ideal.

I think there's a reasonable amount of heft to this set of principles, especially when you consider two other contestable issues. Firstly, polygamy. The OT as a whole seems to permit it. However, (i) it's not the Edenic ideal, (ii) through the OT narratives, polygamy is always shown as a bad idea with bad consequences, (iii) the Law restrains, accommodates, and improves polygamy, it does not mandate it. Secondly, slavery. Again, (i) it's impossible to do a good-faith reading of Eden and think that slavery is God's ideal; (ii) the OT narratives treat slavery as part and parcel of the world, but they do not depict slavery as a good thing, (iii) the Law definitely restrains, accommodates, improves, and I would say provides a liberationist ideal for slavery; (iv) the OT narratives and the depiction of God's character work to highlight God as the liberator of slaves.

I think it's not unreasonable to read the OT Law in this situation along the same lines. That war is not an Edenic ideal (!), but that the Law accepts its existence, regulates and improves it. But the OT on a whole does more than this. As Sprinkle argues, the OT is peculiarly (compared to other nations) against militarism. Israel had a relatively egalitarian social structure, was to have no standing army or developed military technology, and generally was to expect God to fight its battles for it.

Of course, everyone asks about the conquest of Canaan and the apparent commands to commit genocide. It's true, this are very thorny issues. But they are thorny for Just War advocates too. Sprinkle largely follows the work of Paul Copan and Christopher Wright in tackling these questions, and that's a pretty decent approach to a very difficult question. Here are some main points:

The Canaanites were a particularly immoral and wicked civilisation

And, it's God's prerogative always to judge, to give life and take it.

The primary point of the Conquest is to drive them out, not annihilate them.

There is persistent forewarning for them.

Total annihilation is neither exactly what was commanded, nor what was done

Even after all is said and done, the Conquest is a one-time, specific and unique event. It's not a paradigm for Christians.

Instead, as the subsequent chapter goes on to show, the rest of the OT continues to critique militarism and even embrace full-blown nonviolence, if you read the prophetic critiques of Israel as a militarised state.

Then, at last, we get to Jesus. It's kind of easy to argue that Jesus was into nonviolence. It's very hard to argue otherwise, one would think. So, I won't really recap these chapters, except to say that Jesus embodied perfectly in his life and teaching the nonviolence love of his enemies, and that we are called to do precisely the same. Sprinkle's final biblical chapter covers Revelation, which he correctly argues is a weird kind of 'militant' apocalypse in which God's people never carry out violence, but conquer through suffering violence, just as the Lamb conquers through being slain.

Chapter 10 covers the early church. It's well documented that prior to Constantine no early Christian writer accepted violence as an okay thing for Christians. No soldiers, no self-defence. Just total blanket agreement that Christians should be people of non-violent peace. Chapter 11 deals with the classic hypothetical, "what if someone turned up at your door to kill your family, and it was either that or you shoot them?" While chapter 12 works through a range of typical and common objects, with answers.

I don't really intend to convince you in this book review to be a pacifist. Though I am very happy to field questions via comments or reply to the email version of this. What I will wrap up with is this. Jesus' most radical ethical teaching is love for enemies. And his most profound act was to go to the cross, laying down his life, in nonviolent love that embodied redemptive suffering. And the one point that the New Testament is incredibly insistent upon is that we imitate Jesus precisely in enemy-love and in participating in his sufferings. If God is the Lord of History, the Judge of the Living and the Dead, the one who raised Jesus from death and will raise us too, then faithful obedience means following in the footsteps of the Prince of Peace.

Post-Script:

Do I have opinions about the Israel-Gaza-Hamas war, or the Russian invasion of Ukraine? Yes. Relatively informed and reasoned ones.

Do I feel the need to share those opinions on the internet because I think I am an armchair expert in international war? No. In private conversation, sure, I’m happy to give you my opinions, but I don’t think one more op-ed take on current affairs on substack is going to do anybody much good.