“More than three hundred years ago your forefathers were taken from the western coast of Africa as slaves. The people who dealt in the slave traffic were Christians. One of your famous Christian hymn writers, Sir John Newton, made his money from the sale of slaves to the New World. He is the man who wrote ‘How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds’ and ‘Amazing Grace’—there may be others, but these are the only ones I know. The name of one of the famous British slave vessels was ‘Jesus.’ “The men who bought the slaves were Christians. Christian ministers, quoting the Christian apostle Paul, gave the sanction of religion to the system of slavery. Some seventy years or more ago you were freed by a man who was not a professing Christian, but was rather the spearhead of certain political, social, and economic forces, the significance of which he himself did not understand. During all the period since then you have lived in a Christian nation in which you are segregated, lynched, and burned. Even in the church, I understand, there is segregation. One of my students who went to your country sent me a clipping telling about a Christian church in which the regular Sunday worship was interrupted so that many could join a mob against one of your fellows. When he had been caught and done to death, they came back to resume their worship of their Christian God. “I am a Hindu. I do not understand. Here you are in my country, standing deep within the Christian faith and tradition. I do not wish to seem rude to you. But, sir, I think you are a traitor to all the darker peoples of the earth. I am wondering what you, an intelligent man, can say in defense of your position.”

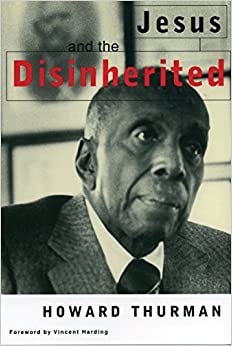

Thurman, Howard. Jesus and the Disinherited (pp. 4-5).

What does, what can, the religion of Jesus say to people "who stand with their backs against the wall". This is the question that Howard Thurman engages with in his short yet powerful book. Thurman (1899-1981) was a prominent theologian and civil rights leader of the last century. This book was perhaps one of his most influential, and was highly prized by Martin Luther King.

The question that Thurman tackles is one that gripped me at a young age. Not because I truly was among the disinherited of the world, but like a good lumpenproletariat anarchist, I sympathised with their plight. And it's still a question I think of profound importance - what does Jesus have to say to the oppressed, downtrodden, marginalised, and suffering of this world?

The book moves across five chapters. In the first, Thurman turns our attention directly to Jesus, situating him. He reminds, and depicts, Jesus as a Jew, a poor Jew, a member of a minority in the midst of an occupying majority force. The combination of the three, and especially the last, means that Jesus occupies the place of so many other minorities - how to survive in a world of a hostile majority - what was Jesus' attitude to the occupiers? For Thurman, the answer is a the humility and authentic realism that denies the occupier the ability to determine his inner life, thus stripped the oppressor of their primary weapon(s). It is nonviolent resistance, love for enemies, and a profound inner resolve. This chapter moves on to consider how the religion of Jesus became the instrument of so much appreciation for so many, but I will leave that for you to read.

In chapters 2-4 Thurman considers three aspects, "hounds of hell" that hound the life of the disinherited: fear, deception, and hate. In these, Thurman's analysis of the condition of the disinherited is compelling. He speaks, for instance, of the pervasive and ever-present fear that comes from an existence in which violence is always possible, and always on one side. How do people live when they can never fight back?

In such physical violence the contemptuous disregard for personhood is the fact that is degrading. p28

There are few things more devastating than to have it burned into you that you do not count and that no provisions are made for the literal protection of your person. p29

In such circumstances, fear itself becomes a weapon of oppression, and the disinherited learn to live forever cowering, but this fear becomes a "death for the self". Can Jesus say anything to such fear? Yes, says Thurman. Jesus' great contribution here is that God cares for the individual. The great summation of this is in the Sermon on the Mount. The identity of a person as a child of God, grants an integrity that destroys fear, and so to give in to the fear of death becomes itself a denial of the integrity of the person before God. It is this knowledge that provides a confidence that transcends fear and death alike, and puts him on a level with his oppressors.

When one side holds power, the other side learns to lie. Such is the analysis of Deception. It is a truism, true of groups, true of individuals, true of children and parents. We learn to negotiate our powerlessness in the hands of others, by subverting the truth as a survival mechanism. When one's life is at stake, morality goes out the window. So what to say about truth-telling for those who live daily under threat of death.

It is only when people live in an environment in which they are not required to exert supreme effort into just keeping alive that they seem to be able to select ends besides those of mere physical survival. p59

For Thurman, the only real possibility, having discarded several others, is to shift one's major concern from mere survival. Only in doing so does "complete and devastating sincerity" become possible, your yes yes and your no no. Jesus was not naive though; he placed our life in the ever-presence of the living God. And relentless sincerity has another effect - it strips power from the strong and forces them to relate as human being to human being. Here is the moral power of truth-telling about oneself and one's enemy.

The third hellhound is Hate. The hate of oppressor for oppressed, and oppressed for oppressor. Thurman rightly notes that Christianity's analyses tend to be shallow. His, though he does not say so, digs deeper. For Thurman, "hatred often begins in a situation in which there is contact without fellowship, contact that is devoid of any of the primary overtures of warmth and fellow-feeling and genuineness." (p65) It is the failure to treat person as person. This becomes 'unsympathetic understanding' and then ill will, and then "hatred walking on the earth". And hatred destroy us from the inside out.

Jesus rejected hatred. It was not because he lacked the vitality or the strength. It was not because he lacked the incentive. Jesus rejected hatred because he saw that hatred meant death to the mind, death to the spirit, death to communion with his Father. He affirmed life; and hatred was the great denial. p78

The answer to hatred is found in Thurman's final chapter: Love. The Love-ethic of Jesus embedded in "Love your neighbour as yourself" and embodied in the parable of the Good Samaritan. Jesus in his life had to live this - in relation to hostility from fellow Jews, in relation to Samaritans, and in relation to Rome. Thurman analyses "the enemy" in three categories. Firstly, the personal enemy. This is the person who already exists within our networks - our village, our family, our church. It is this level that we so often think about when talking about love your enemy. Indeed, so much of our preaching and teaching is about forgiving and reconciling in such contexts.

But there are two other categories that we ought to think of, and probably don't. "The second kind of enemy comprises those persons who, by their activities, make it difficult for the group to live without shame and humiliation." p83. Thurman has in mind the traitors, like the tax-collectors of Israel. There are always, for the disinherited, such people - those willing to betray their own to gain some advantage. And the only way to love these people and win them is to get at their heart, get at their simple and bare humanity.

The third category is Rome. It is the general category of a wholly other group as enemy. And "To love the Roman meant first to lift him out of the general classification of enemy. The Roman had to emerge as a person." (p85) We must learn to take an individual as an individual, and love them not as a class. And then learn to apply that to the class as a whole. That is, to come to respect each and every enemy as a person.

Thurman tells the story of the Roman captain who comes to Jesus looking for healing for his servant. I had never thought of the story quite in this light before. His great need humbles himself to come to his enemy, and Jesus receives him as a person. It is the white slavemaster coming to the enslaved Black man or woman, the French colonizer coming to the Berber, the British colonial coming as supplicant to the Aboriginal person, each act involving the humility born of great need. And in that need, Jesus meets them and treats them as they ought to be. This is love, not in the abstract of the general, but in the particular, and yet its particularity makes possible the universal.

What, then, is the word of the religion of Jesus to those who stand with their backs against the wall? There must be the clearest possible understanding of the anatomy of the issues facing them. They must recognize fear, deception, hatred, each for what it is. Once having done this, they must learn how to destroy these or to render themselves immune to their domination. In so great an undertaking it will become increasingly clear that the contradictions of life are not ultimate. The disinherited will know for themselves that there is a Spirit at work in life and in the hearts of men which is committed to overcoming the world. It is universal, knowing no age, no race, no culture, and no condition of men. For the privileged and underprivileged alike, if the individual puts at the disposal of the Spirit the needful dedication and discipline, he can live effectively in the chaos of the present the high destiny of a son of God. p98-99