I remember it at the time, the news reports of yet another school shooting in the US. This time, five young girls in a small schoolhouse in Pennsylvania. What struck me then, and the world, was the Amish response - to immediately forgive the killer and forgo any desire for revenge or expression of anger. It's that tragedy that birthed this book.

The Amish, and several other Anabaptist groups, are a gift to the rest of us because they show us what an alternate community can look like. Even if we don't embrace their beliefs and way of life, we are all the better for learning from them. I picked this book up because there's two things I wanted to think on more deeply - how to cultivate a persistent, prevalent, deep attitude of grace and forgiveness in myself, and how we build thicker, more resilient communities of grace.

Part one

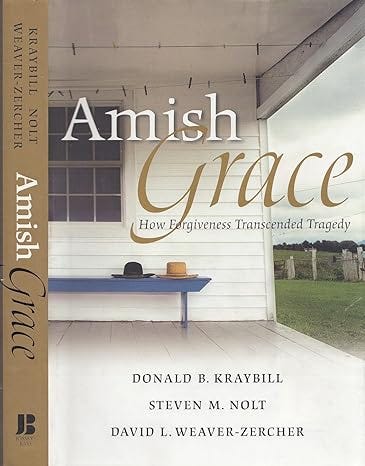

This book is also a harrowing read, at least the opening chapters. On Oct 2, 2006, a man shot ten girls, aged 6-13, in an Amish schoolhouse in Pennsylvania, killing five. The events of that day are told in chapter two, and it's the most difficult chapter to get through. Before that, the authors spend a little time in chapter one recording their arrival at the scene and a little bit of Amish culture and their situation in Lancaster County. The authors are professors who have written extensively on Amish history, culture, and practice, and the book as a whole is an attempt to help us understand the how and why of Amish response to this tragedy, sociologically and in terms of the Amish own theology.

Chapter three walks us through the aftermath of the tragedy (also tear-jerking), before chapter four deals with the 'surprise' - that the Amish responded with immediate forgiveness, which showed itself in care, concern, outreach, and embrace of the killer's widow and family. Forgiveness for the Amish is not something done at arm's length, it is the whole hog. And this stunned America (and the world). Chapter five covers reactions, on the whole positive, amazed, awed even. Some critiqued them.

Part two

Part two begins to look at how and why the Amish forgave like this, and in fact forgive like this. Chapter six examines how typical, or not, the forgiveness shown in the fact of the massacre is. The authors work through a number of other incidents involving Amish people, and give us accounts that show that this type of forgiveness is indeed typical of the Amish. Warning, this chapter is also very moving.

The authors talk about culture as like a 'musical repertoire' - you have this set of pieces you know incredibly well, and you dive into that storehouse to play. So too, the habits of our culture are what we draw upon to respond by default. They are our 'go-to' actions. That's what we see in these narratives - forgiveness is offered as a first response. The first story here is a mother on the scene of an accident directly responding to the culpable driver who hit her five-year old, proclaiming her forgiveness. The story that follows, a 17yo who killed a newlywed bride with his car, experiencing the profound embrace of her family, even her widower husband, as Amish forgiveness. The authors here also explore how Amish distinguish consequences from revenge, in their personal approach and relation to the legal system. There's also a recognition here that forgiveness, even when offered directly and immediately, isn't necessarily easy, and doesn't discount the deep emotions and hurt involved.

Chapter seven begins to explore the roots of forgiveness. What is it in Amish culture that creates this forgiveness? It is, the Amish themselves point out, the teachings of Jesus. The authors of this book highlight all the usual New Testament passages, which the Amish themselves refer to. But is that all? They make some particular points here:

For the Amish, "the primary expression of faith is following - even imitating - Jesus" in a way that it is/may not be central in other Christian traditions. In my words, there's a very heavy emphasis on imitation of Christ as the ethical core of Christian practice.

This works itself out in their diet of Scripture - much more NT than OT, much more Gospel than letters. Much more Matthew than anything else.

Naturally, Mt 18 features prominently, as does the Sermon on the Mount.

And the Lord's Prayer...

The section on the Lord's Prayer is fascinating. Sure, it's very clear in there, the connection between forgiving others and God forgiving us. And it's there in the rider that follows, Mt 6.14-15. But it's the place of the Lord's Prayer in Amish life that is so interesting.

The Amish pray the Lord's Prayer almost constantly. They tend to eschew spontaneously composed prayers, and so they use the Lord's Prayer for almost everything. In services, they may use some old written prayers from a prayer book, but it includes the Lord's Prayer. When there are times of silent prayer, what do the Amish pray in their heads? The Lord's Prayer. Family devotions? Lord's Prayer. Meal times? Lord's Prayer.

Lastly in this chapter, the authors explore the theology of forgiving to be forgiven. Here is something I would disagree with, but let's be clear - the way that Mt 6.14-15 and 18.35 read strongly suggest that being forgiven by God is contingent upon forgiving others, and the Anabaptist and Amish way of reading takes this at face value - if you won't forgive others, you can't be forgiven.

From where I sit, this is wrong because of salvation by faith. But, I think there is something very important to take away from the Amish, and Jesus' strong words. Failure to forgive is symptomatic, not causative, of a failure to receive God's forgiveness appropriately and be moved and changed by it. For the Amish, however, "see God's forgiveness of human beings as both present and future, an offer of grace that can be secured only if one shows grace to others".

Chapter eight, "The Spirituality of forgiveness", considers how other cultural elements play into this. All through the book we see the emphasis of community and collectivism. This chapter also explores the very strong notion of "yieldedness" - yielding to God, to the church, to one another. How this manifests in submission to suffering, to accepting providence, to non-resistance, and to giving up efforts to revenge or seek justification.

Also in this chapter we explore the strong role that story-telling and martyrology play. The classic Anabaptists were, proportionally, heavily martyred during the Reformation and following years. And their stories are gathered and treasured in Martyrs Mirror, a massive tome detailing their stories and deaths. I suppose it is the Anabaptist version of Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Forgiveness, as the authors point out, features prominently in these stories.

This got me reflecting on hagiography in general. Past generations read and treasured such stories. I would say that in more recent generations, certainly since the emergence of the modern missions movement from the 17th century onward, the shift in Christian hagiography was to missionaries as exemplary Christians. That, in more recent decades, has thankfully faded as we have learnt to see missionaries as more ordinary mortals. Instead, however, we have mostly embraced a celebritisation of successful pastors as writers and speakers, which is really a very secularised form of elevation and idolisation. But our model of "successful Christian life" is quite far removed from many of our forebears, and certainly the Amish.

We need stories, and we need inspiring exemplars. At the same time hagiography almost always involves distortion, or at least selective retelling. Heroes become heroes by becoming less than fully human, even as they appear more than human.

Chapter nine moves on to the difficulty of forgiveness. I think that because the Amish forgave, and forgive, so quickly, this seems to undermine the authenticity of that forgiveness. As if it signifies that the pain and hurt and suffering is somehow minor and easily forgivable. No, it's not. The death of your daughter to a school shooter is not a minor hurt, nor an easy to forgive thing.

So, how do they foster this? Part of it is the "primacy of the community over the individual". the "letting go of self-will" as one Amish woman put it.

The Amish celebrate communion twice a year, with a month long preparation season. Two weeks before Communion Sunday, they have a worship service called "Council Meeting", in which there is consistent and abundant teaching from all of Matthew 18. All the members are admonished to forgive any wrongs and sort out grudges. Failure to forgive others leads to those members attending, but not participating, in communion. But a serious disagreement of more than just a couple of individuals can lead to delaying the Communion, for weeks or months if necessary, to sort out the community relationships. In this way the Amish take Communion, Matthew 18, and 1 Cor 11 very seriously indeed.

Despite all this, forgiveness can still be hard, and the Amish admit as much. They recognise their humanity and fallenness. They often struggle more with the minor grudges and close relationships, than the big sins and the outsider. But they are all committed to their community, mutual relationship, and forgiveness. They work hard at it.

Part Three

Part 3 moves from the practices of forgiveness, to the meaning of forgiveness for the Amish and for the rest of us.

Chapter ten turns to the question of what is forgiveness. This overlaps, obviously, with other books I've read in the past couple of years. The authors here draw on the work of Robert D. Enright and Everett L. Worthington Jr., both of whom are involved in clinical research on forgiveness (yes, you can be a researcher in forgiveness). Their definitions of forgiveness involve the taking the offense seriously, the moral right to anger, and the victim giving up their right to anger and resentment. It is a gift to the offender. It is also unconditional.

When we have a robust definition of forgiveness, we can respond to the critics of the Amish and of forgiveness in general, because often those critiques miss the mark. Forgiveness isn't pretending, forgetting, condoning, or excusing. Nor is forgiveness the same as reconciliation (which requires repentance and the restoration of relationship), nor pardon (the release of the offender from consequences or punishment).

The authors here also explore anger in the Amish situation. In interviews with the families and other affected Amish, there certainly was anger, but culturally the Amish directed that not at the killer, but at the evil itself. Amish have strong cultural and theological directives that speak against anger, and so tend to deflect it from the person themself. The authors also point to a distinction between anger ("the first response to hurt") and resentment ("continually 're-feeling the original anger'"). The Amish are very clear that while people may have initial angry feelings, both acting out of anger and harbouring resentment are wrong.

The authors also explored the question of the apparent instant or immediate forgiveness of the Amish after the massacre. They highlight two things. Firstly, they draw our attention back to the strong community orientation. For the Amish, forgiveness involves the community forgiving the killer and his family. In what sense? In the sense that they (a) forewent the right to revenge. That initial declaration was then expressed by gracious acts - visiting his family, being present at his funeral, and contributing to support the killer's widow. This maps to a distinction that Worthington makes between decisional forgiveness, "a personal commit to control negative behavior", and emotional forgiveness, "when negative emotions - resentment, hostility, and even hatred - are replaced by positive feelings". Decisional forgiveness can, and was, offered in an instant. Emotional forgiveness is a process. The Amish declared forgiveness immediately, then put it into practice in gracious deeds, but they also made clear in interviews afterwards that they repeatedly forgave by practising emotional forgiveness in their hearts, over time.

Lastly in this chapter, what did it mean to forgive the killer's family, since they weren't culpable? Forgiveness in this sense meant expressing sympathy for both the grief and shame of his family, and foregoing any grudge-bearing or bitterness towards that family. It was the act towards relationship with them.

>> Genuine forgiveness takes a lot of work - absorbing the pain, extending empathy to the offender, and purging bitterness - even after a decision to forgive has been made. Amish people must do that hard work like anyone else, but unlike most people, an Amish person begins the task atop a three-hundred-year-old tradition that teaches the love of enemies and the forgiveness of offenders" p140

Chapter eleven turns to the practice of shunning. If the Amish are so forgiving, why do they do this? This is a really valuable chapter for its insight into Amish practices and culture. Forgiveness, recall, is an unconditional gift. Pardon requires repentance, and so in Amish contexts this really involves church members. In the Amish context, when someone confesses, and accepts the church and community's discipline, they are restored to fellowship. In this sense they take Mt 18:18-20 very seriously. This extends not just to clear sins, e.g. adultery, but to violations of the communities' standards. Because violating those standards is an act of selfishness for someone who has agreed to stand by them.

If I, for instance, belong to a community that has decided that mismatched shoes are a sign of vanity, and I choose to wear mismatched shoes, then that is a sin. Not because of the shoes, so much as because I am willfully defying the community that I voluntarily chose to join and submit to. My selfishness is the sin.

But the Amish are serious about forgiveness and pardon - a person who confesses is pardoned, and the members commit not to bring up this sin again nor to hold it against them. A member who refuses to repent, refuses to confess, refuses to change their behaviour and submit to discipline will, eventually, be excluded (e.g. shunned). This is Amish church discipline. It's intent is still restoration. It does not involve severing all social ties, but certainly major ties. Shunning applies to members, not outsiders. Outsiders and shunned members are forgiven. But only members are pardoned, because only members can be restored to fellowship within the church through repentance.

One reason this is so hard to practise outside such communities, in more 'normal' churches, is simply that the ties of our community are so weak. You can excommunicate someone and they can go to the church down the road. Or, with defiant individualism, they simply don't feel any real loss of community. I don't think there's an easy fix to this, but the Amish practice in itself makes clear something I think is more broadly true - the need for a robust set of distinctions between forgiveness, pardon, discipline, repentance, and reconciliation. Each is distinct and confusion between them does not help us.

Chapter twelve covers a fair amount of terrain: grief, providence, and justice. It begins by talking through the experience of grief at the death of the five girls, and how this was expressed in particularly Amish ways. Firstly, the regular and frequent visits by community members; secondly, the women dressing in black for a length of time set by their relationship to the deceased; thirdly, the writing of memorial poems; fourthly 'circle letters' between Amish in different states with similar experiences.

I couldn't help relating this to how I've been learning about keening practices in traditional Gaelic culture. Just in terms of how structured, ritualised forms of public grief provide space and structure for grief to be expressed, and to be witnessed. We (modern westerners) have generally privatized grief and are embarrassed by public displays of it. I am thinking now of the several of my friends who have lost parents in the last couple of years. We have lost something by not having rituals of grief and mourning beyond the funeral.

The following section grapples with providence - how could God let this happen? The authors mainly explore everyday Amish views of providence, which intersect with broader Christian views of providence, but through this all is what I call "a strong view of providence", namely (a) that God is ultimately in charge, and (b) he is good and works for good. They looked for good to come out of evil. They also, perhaps more readily than the rest of us, rested in divine mystery - that there comes a point where we don't know and won't know and must fall silent.

The last section in this chapter turns to justice. The Amish have a strong sense that judgment lies in God's hands, not ours, and so revenge and the desire for revenge are not appropriate. More than this, Amish humility is epistemic - they tended to say that they didn't, and couldn't know anything about the killer's eternal state, or even their own. Amish don't pronounce that they are saved.

Here is another point at which I disagree with the Amish, I think their humility is "over-realized". I would say that one can, in humility, point to the explicit promises of God and his faithfulness, and know with confidence that because of Christ's sacrifice one is saved. The combination of a certain humility, and thus unwillingness to affirm one's eternal security, along with the Amish reading of God's forgiveness being contingent upon our obedience (including forgiving others' sins), pushes them back to a works-based righteousness, which is the opposite side of the Reformation pendulum, the mirror-image of Roman Catholicism.

Rather, I would say, it is precisely the profound assurance of God's love and forgiveness in the cross, that ought to be the ground and spring of our forgiveness.

Chapter thirteen turns to the question of what we, the non-Amish, may learn from the Amish in this respect. And the authors make the very good point that we cannot simply "strip-mine" forgiveness from the Amish. "their commitment to forgive is intricately woven into their lives and their communities" (p174).

I think this is very much true when we turn to the question of community. I think many of us want thicker communities, but we are highly individualistic, and the price of the communities we say we want is often simply too high - we certainly aren't willing to commit and subject ourselves to the kind of communitarianism the Amish exemplify. I do think there might be a middle way, a place with thicker community ties, but not quite so collectivist as the Amish.

But, I (and the books' authors) do think there are take-away lessons to carefully extract and apply. We might, indeed, form cultures that nourish grace and (dare I say it) stigmatise revenge and grudge-bearing. "We are not only the produces of our culture, we are also producers of our culture. We need to construct cultures that value and nurture forgiveness" (p.182)

The book closes with an Afterword on the lives of those after the shooting. And then what is a profoundly moving section, an interview from 2010 with the killer's mother. What stands out here (for me) is the first-person account of how the Amish came to visit her family immediately and extend grace, how the first people to greet her at the gravesite for her own son were parents of those slain, how both her family and the Amish had kept up practices of visiting from the start and ever since. Her ability to forgive her son, and the grace shown her through sorrow, are profound.

I ended up getting so much more out of this book than I had expected, which is why this review is so long - I wanted to share with you all much of what I'd gleaned, and some of my own reflections along the way. This particular tragedy, which the local Amish simply refer to as "the Happening", still speaks even today. We certainly don't have to become Amish, but we can learn much from them. I will let the killer's mother have the last word:

A root of bitterness never brings peace. A root of bitterness is worse than any cancer in our body. (p197)